Ever felt your heart race before speaking to someone new? That’s not unusual. For many people, it’s just nervousness. But for those with social anxiety disorder, it feels like standing on a stage under harsh lights, every eye watching. This condition isn’t just emotional—it’s neurological.

The human brain shapes our reactions to fear and judgment. When anxiety dominates, it can rewire how the brain functions. Understanding these changes helps explain why social anxiety feels so overwhelming.

Let’s explore how does social anxiety affect the brain and what that really means for those living with it.

What Is Social Anxiety Disorder?

Social anxiety disorder, or social phobia, is more than shyness. It’s an intense fear of social or performance situations. People with this disorder fear embarrassment, criticism, or rejection. Everyday interactions—like talking to a cashier or attending a meeting—can trigger severe anxiety.

This fear can interfere with relationships, work, and education. Unlike ordinary nervousness, it doesn’t fade quickly. It lingers, affecting confidence and behavior.

Scientists classify it as a chronic mental health condition, often beginning in adolescence. Genetics, brain structure, and life experiences all play a part. The brain’s wiring becomes highly sensitive to perceived threats, even when none exist.

Areas of the Brain Affected by Social Anxiety

Social anxiety involves several brain regions working overtime. These areas handle emotion, memory, and response to threat.

The Amygdala: The Fear Center

The amygdala acts as the brain’s alarm system. It detects danger and triggers emotional responses. In people with social anxiety, it becomes overactive. Simple social situations feel like emergencies.

When someone fears judgment, their amygdala lights up as if facing real physical danger. This heightened activity explains racing hearts, sweating, and trembling. The body thinks it’s under attack, even in harmless situations.

The Prefrontal Cortex: The Rational Mind

Next comes the prefrontal cortex—the reasoning part of the brain. It helps us control emotions and make rational decisions. In social anxiety, this area doesn’t regulate the amygdala effectively. The fear response grows stronger because logic takes a back seat.

People might know their fear is irrational. Yet, their brain keeps sending signals of danger. This imbalance between emotion and logic traps them in anxious loops.

The Hippocampus: Memory and Emotion Storage

The hippocampus stores emotional memories. In those with social anxiety, it can exaggerate past negative experiences. The brain remembers embarrassment more vividly than success.

This memory bias reinforces fear. For example, a single awkward moment during a speech might define every future attempt. The hippocampus pairs that memory with fear, making similar situations stressful.

The Fight-or-Flight Response

The fight-or-flight system protects us from danger. It’s a survival mechanism, releasing stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. These chemicals prepare the body to react quickly.

In social anxiety, the same system activates unnecessarily. Meeting someone new can cause the same physical reaction as facing a wild animal. Heart rate increases, muscles tense, and breathing quickens.

This constant alertness exhausts the body. It becomes hard to relax or think clearly. When this happens repeatedly, the brain adapts to expect threat even when none exists.

Imagine attending a party. Your body feels as if you’re running from danger, though you’re just talking. That’s the brain’s misfired alarm—trained by anxiety.

The Brain's Feedback Loop

Social anxiety creates a cycle that strengthens itself over time.

Step One: Anticipation

Before any social event, the anxious brain predicts disaster. It imagines embarrassment or rejection. The amygdala becomes active, and physical symptoms start even before the event.

Step Two: Avoidance

To escape discomfort, many avoid social situations. While avoidance brings relief, it also reinforces fear. The brain learns that staying away prevents danger, confirming the false belief that social contact is unsafe.

Step Three: Reinforcement

When avoided situations seem “safe,” the brain rewards avoidance. This feedback loop strengthens anxiety pathways. Over time, it becomes automatic. The more someone avoids, the harder it becomes to reengage.

Breaking this loop requires retraining the brain. Through gradual exposure or therapy, individuals can reshape how their brain reacts to social triggers.

Long-Term Brain Effects

Chronic anxiety doesn’t just affect mood—it changes brain chemistry and structure.

Cortisol Overload

Prolonged stress leads to high cortisol levels. This stress hormone, when constantly elevated, harms brain cells. It can shrink parts of the hippocampus, impairing memory and learning.

Over time, emotional regulation weakens. The brain struggles to distinguish between real and imagined threats.

Neural Pathways and Plasticity

The brain forms new connections based on repeated behavior. When fear dominates, anxious pathways strengthen. The more someone worries, the easier it becomes for those same fears to resurface.

Fortunately, neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to rewire—offers hope. With treatment and practice, the brain can form calmer, more balanced pathways. It’s like teaching an old alarm to stop going off every time the wind blows.

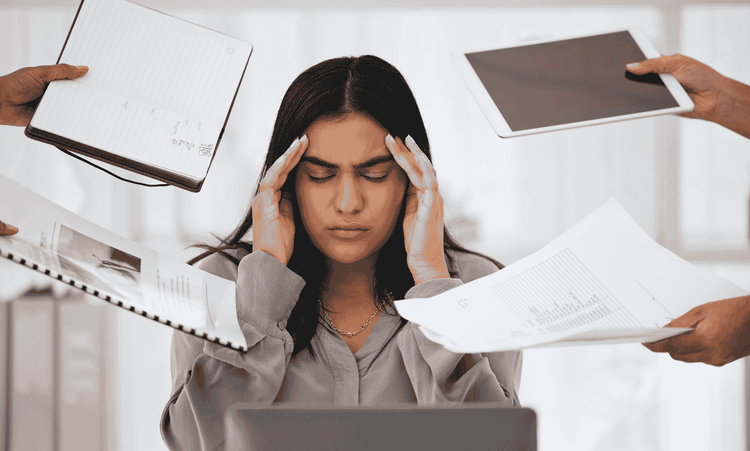

Impact on Daily Life

Long-term anxiety affects focus, sleep, and decision-making. The constant state of vigilance drains mental energy. Small choices become stressful. Even positive experiences lose their joy when the brain is stuck in fear mode.

How Is Social Anxiety Disorder Treated?

Treating social anxiety often involves a combination of therapy, medication, and support. Each approach targets the brain differently, aiming to restore balance.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy, especially cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), helps reframe negative thinking. CBT teaches individuals to challenge irrational fears and change behavior patterns.

For instance, a therapist might help a patient gradually face feared situations. Over time, this retrains the brain’s fear response. It’s not about erasing fear—it’s about teaching the brain that social situations aren’t dangerous.

Therapists may also use mindfulness-based strategies. These techniques focus on staying present instead of imagining worst-case scenarios. Regular practice reduces overactivation in the amygdala and strengthens rational control in the prefrontal cortex.

Medication

Medication can balance brain chemistry. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed. They increase serotonin levels, improving mood and reducing anxiety.

Beta-blockers may also help with physical symptoms like shaking or rapid heartbeat during stressful events.

However, medication isn’t a cure. It works best alongside therapy. The goal is to help individuals manage symptoms while they rebuild healthier thought patterns.

Support Groups

Humans are social creatures. Support groups remind people they aren’t alone in their struggles. Sharing experiences reduces isolation and builds confidence.

In these groups, participants can practice social interaction in a safe space. Over time, this experience weakens the brain’s link between social situations and danger.

Hearing others’ progress also motivates continued healing. Emotional support makes recovery feel achievable rather than distant.

Conclusion

So, how does social anxiety affect the brain? It alters how the mind perceives and responds to social threats. The amygdala becomes overactive, the prefrontal cortex loses control, and the body stays in survival mode.

Yet, the brain is adaptable. With therapy, medication, and support, it can change. The same neuroplasticity that fuels anxiety can also build calm.

If you or someone you know struggles with social anxiety, remember—this isn’t weakness. It’s a pattern the brain can relearn. With the right guidance, the fear that once ruled can become manageable, even conquerable.

Your brain can find peace again—it just needs a chance to retrain itself.